Emblem of the Month

Emblem of the Month, n. 009

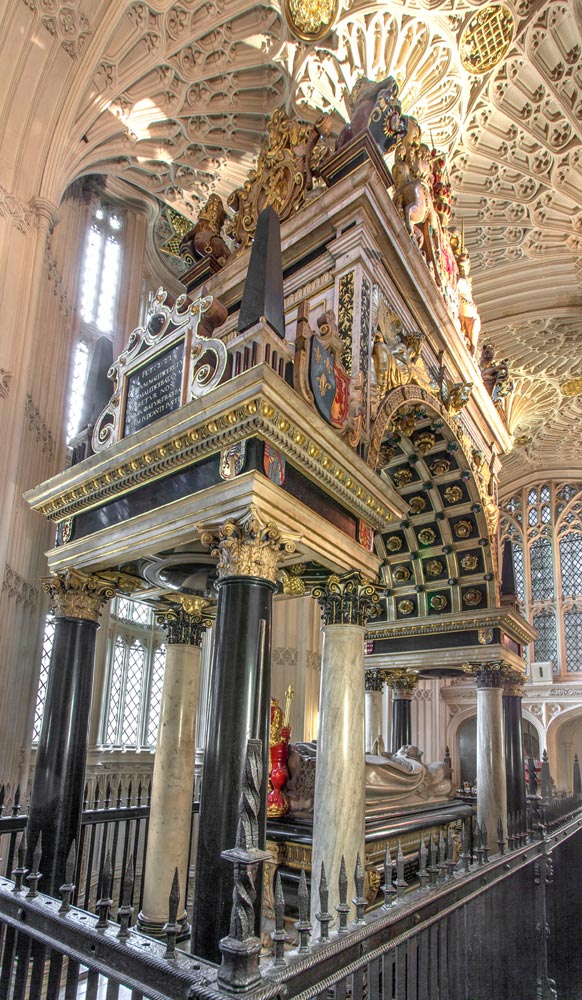

Memorialising Mary: The Monument to Mary Queen of Scots

Many of us who saw Josie Rourke’s recent (2018) film about Mary Queen of Scots, starring Saoise Ronan and Margot Roberts, will remember that scene, quite late in the film, where the two Queens meet at some undisclosed location in the north of England. At least one or two critics noted that this meeting, for all its drama, never happened, and academic historians and pedants, such as myself, worried about the falsification of history. But Josie Rourke wasn’t the first or only scriptwriter to dramatise such a meeting, for in 1801 Friedrich Schiller had already brought them together on stage in order to dialogue their differences in his play Maria Stuart – and this is the play which inspired Donizetti’s famous opera in 1835. The closest the two queens actually got to a meeting, however, was only posthumously when, shortly after the Union of the Crowns in 1603, Mary’s son, James VI of Scotland and I of England, decided to erect the imposing monuments to both queens here in Westminster Abbey.

So the question arises, what were James’s motives in bringing together here in Westminster not only the mortal remains of his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, but also those of his predecessor on the English throne, Elizabeth of England, who had tried his mother on charges of High Treason, and signed the warrant to chop off her head. And when I say ‘mortal remains’ I mean that literally because, in order to build the two imposing monuments that have now become one of the high points of any visit to the Abbey for sightseers and tourists, King James had to disinter both of their bodies from their initial burial sites –– elsewhere in the Abbey for Elizabeth, and much further away in Peterborough Abbey for Mary Queen of Scots which is where she was laid to rest following her execution in nearby Fotheringhay Castle in 1587.

Now at first sight King James’s motives might seem clear enough. In 1603 the Stewart kings of Scotland succeeded Elizabeth Tudor on the English throne precisely because England’s “Virgin Queen” had failed to fulfill the primary duty of any female head of state in a hereditary monarchy, which is of course to give birth to a legitimate male heir to the throne. That’s not any easy thing to do if you remain a virgin. So, we may conclude, James built both monuments to his two royal predecessors in order to commemorate both of those monarchs who wore the two crowns he now inherited, and to reconcile the two nations whose long historical independence and recurrent conflicts had been brought to an end in a happy amalgamation that we still call the “United Kingdom”. Full unification of the two nations and their parliaments had to wait for another 100 years, of course, but 1603 and the Union of Crowns is effectively its beginning.

However, commemorating both his predecessors was never going to be that straightforward. Not only because one queen had chopped off the other’s head, but also because one queen was Protestant and the other Catholic. Now it is certainly true that, as most of the Abbey’s Friends and Guides who are here tonight will know, since 1534 the Abbey has enjoyed the status of a Royal Peculiar, having been refounded by Elizabeth as a Collegiate Church, exempt from the jurisdiction of archbishops and bishops, neither a cathedral nor parish church but subject only to the sovereign.

Nevertheless Catholics were still persecuted as recusants in England, and James’s commissioning of the tomb to his martyred mother in 1606 was unlikely to be viewed without some surprise, only less than twelve months after the Gunpowder Plot, in which Catholic conspirators, notably Guy Fawkes, had attempted to blow up the Houses of Parliament, just across the road from where we are now sitting.

James’s attempts, as Head of the established Church of England, to plot a via media between what he saw as Puritan extremism on the one hand, and toleration of recusant Catholics on the other, have been extensively documented and studied by historians, as also have his foreign policy objectives in attempting to negotiate an equally conciliatory foreign policy for Britain’s relationships with continental Europe. The 1604 Treaty of London officially ended the war with Spain for which no Peace Agreement had been signed since the Armada victory in 1588. On the other hand there was strong support at home and abroad for him to pursue policies that would support the growing European attempts to make Britain leader of an anti-Hapsburg Protestant League. Either of these alternatives held equally problematic consequences not only for Britain’s place in Europe, but also for the royal marriages of whichever of James’s children –– Henry, or Elizabeth, or James –– would happen to succeed him. Monarchy, after all, is all about breeding. The fact that James’s wife, Queen Anna of Denmark, had some years previously converted to Catholicism meant that attempts to reinforce the anti-Jesuit Act of 1584, which ordered that all Roman Catholic priests in England should either be expelled or executed, were not successful. Although Act was not repealed Stuart policy remained more well-disposed towards religious toleration than Elizabethan policy had been. Needless to say, all these issues have been intensively researched and debated in academic histories.

But this evening I want to just alert you to some recent discoveries of my own which shed further light on these issues, but which you won’t find recorded as yet in any of the literature on early Stuart history or on the Westminster Abbey monuments. These discoveries relate to just two mall details that I want to draw your attention to tonight in the long Latin inscription that we can read (if we have enough time, good eyesight, and read Latin) on Mary’s monument. I cannot show you the inscription right now, but if you wanted to follow up on what I’m going to say, you can easily find it quoted in full, with a helpful English translation, on the Abbey Website.

My first Eureka! moment came when I read the following lines of the inscription:

Victa nequid vinci nec carcere clausa teneri,

Non occisa mori, sed neque capta capi.

Sic vitis succisa gemit fecundior uvis,

Sculptaque purpureo, gemma decore micat.

“Conquered, she was unconquerable, nor could the dungeon detain her; slain, yet deathless, imprisoned, yet not a prisoner. Thus does the pruned vine groan with a greater abundance of grapes, and the cut jewel gleams with a brilliant splendour.”

Sic vitis succisa gemit fecundior uvis – “Thus does the pruned vine groan with a greater abundance of grapes”. It was this image that first caught my attention because some years ago – in 2003 – I wrote a book on the embroideries that Mary sewed, mostly during the later years of her life when she was in exile in England, in the custody of the Earl of Shrewsbury and his wife, Bess of Hardwick. Many of these embroideries have survived in the care of the V&A, and many can still be seen on display at Oxburgh Hall, Norfolk. Amongst the most interesting and important of these – for reasons that we shall soon see – is the centrepiece to the Oxburgh ‘Marian Hanging’, and because it’s the key piece of evidence for my argument this evening, I’ve reproduced it for you on your handout.

As you’ll see, this embroidery shows a hand holding a knife, with which it is pruning the leaves of a vine-stem that is laden with bunches of grapes. The Latin motto draws the moral of this emblem, Virescit vulnere virtus (“Virtue flourishes from its wounds”). I think you can begin to see why, if inscribed on Mary’s monument, such a moral might have some potentially interesting implications; Mary’s beheading might have brought some benefits; her wounds may have stimulated new growth (the rare verb viresco means “to grow greener”, “to flourish again”). As I show in my book Mary did not invent this emblem specifically for this piece of embroidery, sewn sometime probably in the last twenty years of her life, in exile, for in 1557, a year before she married François II in France, a medal had been minted and inscribed to “Mary, by the Grace of God Queen of Scots” (MARIA DEI GRATIA SCOTORUM REGINA) – I have also reproduced that on your handout.

You can find out quite a lot more about this particular emblem in my book, but for now there is just one historical record of it that is of the greatest importance for understanding what it is doing in the monumental inscription here in Westminster Abbey. In 1572 we learn that this emblem was cited as evidence in the trial for high treason of Henry Howard, Duke of Norfolk. Mary Queen of Scots had in the preceding couple of years contemplated the prospect of marriage to Norfolk, who was like herself and like all the Howards, a Catholic. But the prospect of such a Catholic marriage between England’s premier Earl, and the dethroned Queen of Scots who seemingly had a strong claim, circumstances permitting, to succeed Elizabeth, if not to actually replace her, on the English throne – raised all kinds of headaches for Elizabeth.

So Norfolk didn’t marry the Queen of Scots, but got his head chopped off, and one of the pieces of evidence which led to this verdict was extracted from Mary’s ambassador and counsellor, John Leslie, Bishop of Ross, who testified that the year before the trial he had been in Howard’s house when one of Mary’s servants delivered to the Duke a love token in the shape of an embroidery “wrought with the Scots’ Queen’s own arms, and a devyse upon it, with this sentence virescit vulnere virtus, and a hand with a knife cutting down the vines, as they use in the spring time: al which worke was made by the Scots Queen’s own hand”.

Anyone who has worked on decorative and artistic objects knows just how rare it is to find good historical records of the way they were created or used in their own day, so when I first came across this it seemed a wonderful record of Mary’s embroidery. But who, you may well be wondering was this Bishop of Ross who witnessed Mary’s emblematic vine-pruning embroidery being delivered to the ill-fated Duke of Norfolk? Appointed Catholic Bishop of Ross in 1566, he had been sent to France by Scottish Catholic nobles following the death of King François to persuade her to come back to Scotland and during her personal reign he became one of her most trusted advisors, entrusted with her jewels and appointed member of her Privy Council. Following Mary flight into England, he defended her cause at York in 1568 and himself devised the policy of her marriage to the Duke of Norfolk, and was appointed as her ambassador to the English Court. On the failure of the Ridolfi plot he was imprisoned in the Tower, which is where this witness statement would have been recorded. In 1572 he published a Defence of the Honour of Marie Quene of Scotland. On being discharged from prison he was banished from England and lived until he was sixty-nine and fathered three children. He spent his last years in France where he was made Bishop of Coutances in 1593 and died in Brussels three years later.

So, discovering John Leslie’s description of the vine-pruning emblem on the Oxburgh ‘Marian Hanging’ was a red-letter day for my own research on the embroideries. But that excitement was, if anything, exceeded by what I discovered when I came to work on Mary’s monument here in the Abbey, for the writer who composed these Latin verses which describe Mary as a vine whose pruning has stimulated greater fruitfulness, was Henry Howard, younger brother of Thomas whose execution in 1572, as we have noted, had thwarted English Catholic plans to put an adherent of the old religion on Elizabeth’s throne. Like virtually all the Howards, Norfolk’s younger brother Henry was a known Catholic. Not only that, but he was one of the most powerful officers of state in Jacobean England, Privy Counsellor, Warden of the Cinque Ports, and Earl of Northampton. He had been closely involved in the state planning, financing and design of the Westminster Abbey monuments.

We seldom know who writes the inscriptions on tombstones –– their purpose is not to earn laurels for their writer but to commemorate the virtues and achievements of the deceased. But one of the details that makes this inscription on the Westminster monument quite distinctive is the fact that, if you look very closely, it ends by signing off with its author’s initials: “H. N. gemens” which means “Henry Northampton, sighing/mourning”. All inscriptions on monuments are honorific: funerary commemorations are laudatory – that is the convention. We should therefore not expect this one to remind us of the high treason of which Queen Marie Stuart had been convicted under English law, nor of her membership of the Roman Catholic Church. A reminder of her statutory right to the succession (‘Mistress of Scotland by law, of France by marriage, of England by expectation’, l.11) might have been uncontroversial or even expected on such a monument for that was what, after all, had brought about the glorious Union of Crowns which the two royal monuments are there to celebrate. The statement that this happy outcome had only been made possible by Queen Mary’s heroic fortitude and suffering, however, is opening the gates to a rather more troublesome and controversial judgement, namely that she was some kind of martyr; and the call for vengeance on those who caused her suffering (‘May the day of death swoop upon the death-dealers. . . may the instigator and perpetrator rush headlong to destruction’, lines 27-28 of the inscription) risks even more controversial conclusions, which the hope that this suffering is what has secured a lasting peace hardly dispels (‘May it be forbidden to slaughter monarchs, that henceforward the land of Britain may never more flow with purple blood’, lines 29-30). Hence this monument surely becomes, for those who can read the Latin, a memorial to Mary the Martyr.

We cannot know whether his use of the vine-pruning emblem means that the Earl of Northampton had seen Mary’s actual embroidery, but there is surely the strongest likelihood that he would have known of the role that it played in the State Trial of his elder brother thirty years earlier, when it helped to secure the conviction that cut off his brother’s head. And the presence in these Latin verses of other allusions that are open to the suggestion that Queen Mary is being commemorated as a Catholic Martyr raises the whole question of how those who read them, and certainly those who authorised them for the tombstone, above all King James himself, understood them or approved them. It is highly unlikely that he would not have done so, since he was a fluent reader and writer of Latin, having been taught by Scotland’s most distinguished neo-Latin humanist poet, George Buchanan, who – as James famously complained – ‘gar me speik Latin ar I could speik Scottis’.

There is one further image in the Earl of Northampton’s Westminster Abbey inscription that refers to an emblem that Mary had used in her embroideries and that was also used on a contemporary medal. It occurs in lines 10-11:

Jure Scotos, thalamo Francos Spe possidet Anglos,

Triplice sic triplex jure corona beat.

[Mistress of Scotland by law, of France by marriage, of England by expectation, thus she is blest by a three-fold right with a three-fold crown.

Mary’s threefold crown is thus identified as including Scotland, France and England, which looks straightforward enough. But this claim to the three crowns also figures in an emblem which Mary had sewn into her embroideries and in this the three crowns are not all equal, for one of them was represented not as an earthly crown but as a heavenly one made up of stars. We cannot illustrate this particular embroidery because it was sewn into hangings for her Bed of State which have not survived, but we can show quite clearly what it looked like since in 1560, many years before she sewed her embroidery, a medal had been issued showing the same device.

This medal was minted in the same year as the Treaty of Edinburgh, drawn up following the defeat of French troops in the Siege of Leith by an English and Scottish Protestant army – a key turning point in relations between the three nations, with the death of Mary’s mother, Mary of Guise, happening in the same year. It resulted in the withdrawal of French troops from Scotland, the end of the Auld Alliance, and a new Anglo-Scottish accord under the Protestant Lords of the Congregation, which hastened the decline of the Catholic Church and the arrival of the Protestant Reformation in Scotland. Mary in France refused to ratify the treaty because it affirmed Elizabeth’s right to the English throne, negating her own claim, which depended on strongly contested arguments about the legality of Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon and his subsequent marriage to Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn. We can therefore see how easily the use of such an emblem in the Westminster inscription might recall this key moment in Scottish history. Even in its own day the emblem might seem politically astute, claiming either a heavenly crown that carries no political weight and testifies only to the young Queen’s pious hopes or, alternatively, symbolising her insistence on retaining claims to the third earthly crown, in England, which the Treaty of Edinburgh had denied. And its relevance to the seventeenth-century Union of Crowns in which that dynastic inheritance had finally been fulfilled by Mary’s son James is surely clear enough.

This emblem of the three crowns had a remarkable afterlife, which I haven’t time to document at all fully here, except to illustrate just one notable exception which is rather uncannily anticipated by something Northampton says in his verses on the monument, in which he reacts with some vehemence to those who shed the blood of Mary Queen of Scots, he pleads “May it be forbidden to slaughter monarchs, that henceforward the land of Britain may never more flow with purple blood (Sic Reges mactare nefas, ut sanguine posthac /Purpureo numquam terre Britanna fluat). So, “Let there be no more regicides in Britain!” Henry Howard could not have foreseen, in writing this, quite how soon Britain would descend into those civil wars which would lead only forty or so years later to the regicide of James’s son and successor Charles I.

It is highly ironic, however, that one of the most influential commemorations of that regicide should make prominent use of the device of the Three Crowns. It makes use of this emblem, moreover, with a notable understanding of its previous history, going back to the Aliamque moratur emblem of Mary Queen of Scots. Just ten days after the beheading of King Charles on 30th January 1649, a book entitled Eikon Basilike (‘Portrait of a Prince’) appeared in defence of the martyred king, and despite attempts of the Parliamentarians to suppress it (attempts which include John Milton’s Eikonoclastes) it proved so popular with Royalist readers that it went through no fewer than fifty-six reprints. Indeed, its portrait of Charles as a Martyr influenced, after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, the addition of ‘Charles the Martyr’ to the Church of England’s official liturgical calendar.

If we look at the title-page you’ll see that it shows the late King Charles I, kneeling in prayer before an altar where a heavenly crown gleams amidst clouds. This is one of three crowns that make up the emblematic syntax that structures the right-hand side of the engraving, for below it on a table (or altar) King Charles grasps a crown of thorns, below which at his feet an earthly crown lies abandoned on the ground. And here, of course, we have the latest reworking of that emblem of three crowns that goes back through the Westminster Abbey inscription. The verses printed with this title page draw the moral:

That splendid, but yet toilsome Crown,

Regardlesly I trample down.

With joy I take this Crown of thorn,

Though sharp, yet easie to be born.

That heav’nly Crown, already mine,

I view with eyes of faith divine.

I slight vain things; and do embrace

Glorie, the just reward of Grace.

I am not suggesting that this highly influential title-page was inspired by Howard’s inscription on Mary’s Westminster tomb, but I think you can see how easily this emblem of the three crowns could be interpreted as a symbol of Martyrdom.

I want to end by just thinking a bit further about King James’s motives for building the tombs to his two royal predecessors in the Henry VII Chapel. These are by no means the only verses commemorating Mary as a Catholic Martyr to have been written at this date, nor is the Earl of Northampton’s inscription the earliest, for shortly after her execution the Jesuit priest (and eventual martyr himself), Thomas Southwell, wrote his densely emblematic elegy for the martyred queen entitled ‘Decease Release’

Alive a Queene now dead I am a Sainte

Once Mary calld my name now martyr is.

And the closeness of Southwell’s emblems to Henry Howard’s is suggested by lines 3-4 of his elegy:

The perish kernel springeth with increase

The lopped tree doth best and soonest growe

Southwell himself died on the scaffold for his faith, and the Catholic church remembers him as a martyr on 21 February every year. His poems were never published in his lifetime, though they did circulate in manuscripts around the recusant Catholic community in England, and it is by no means unlikely that the Earl of Northampton might have read Southwell’s elegy for Queen Mary the Martyr before writing his own on the Westminster Abbey Monument. His connection with the Howards was certainly quite close, for he had been closely attached as priest to the household of Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel when this foremost member of the English nobility was imprisoned in the Tower for professing his Catholicism.

Another elegy for Mary had also already been written in Latin in 1587, the very year of Mary’s execution when a Scots courtier called John Gordon had written his Manes Mariæ Stuartæ Scotorum Reginæ (‘Remains of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots’). This is a long verse elegy, and in 1603, the very year of the Union of Crowns, it was published in London in a limited edition printed by His Majesty’s official printer for Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Gordon was a Scotsman, who had served abroad in the French courts of Charles IX, Henri III, and Henri IV. He was illegitimate son of the last Catholic bishop of Galloway, whose own mother was an illegitimate daughter of James IV of Scotland; hence royal blood flowed through Gordon’s veins. And that is undoubtedly why Mary Queen of Scots had supported his studies in France and his expenses as Gentleman of the Privy Chamber to the three kings who had succeeded Mary’s late husband, François II on the throne of France. Illegitimate or not, he was, after all, her second-cousin.

In 1603 King James invited Gordon back to England to become Bishop of Salisbury, and in 1604 he preached a sermon at Whitehall on the ‘Union of Great Britain, in antiquitie, language, name, religion and Kingdome’. So, we can see how King James must already have had some familiarity with long Latin verse elegies commemorating his late mother at this date. There were thus good precedents for Henry Howard’s Latin verse inscription on her Westminster monument.

And before we dismiss John Gordon from our discussion it is worth mentioning that a few years later, in 1621, a French courtly writer, Adrien d’Amboise, published a book called Devises royales illustrating the emblematic devices of various European kings and queens, including the Three Crowns device of Henri III, which are identified as the crowns of France and Poland, and the third crown up in the sky, Amboise explains, to symbolise the heavenly crown which Henri would only earn through his wise policies in promoting religious reconciliation. It is from d’Amboise that we learn that this celebrated, and most influential device of Henri III was ‘borrowed’ from Marie Stuart, ‘Reine d’escosse,’ and that it was a Scotsman called John Gordon who had bestowed Mary’s device on her bother-in-law, Henri III.

I want to conclude by saying just something about James’s motives for building or relocating some of the other monuments that surround Mary Queen of Scots’ in Henry VII’s chapel, because there is, of course, a wider and intelligible programme which has been well researched in books and articles by Nigel Llewellyn, David Howarth, Peter Sherlock, Julia Walker and others that may well be known to you. The Abbey website provides an excellent introduction to those issues. Surveying this research and summarising its findings will take us back to my starting point this evening, which – you’ll recall – was about the implications of Elizabeth’s virginity for succession to the English throne. As we shall see, the overriding motivation behind James VI/I’s rebuilding or relocation of the mortal remains of his deceased predecessors and relatives in Henry VII’s Chapel was to compare and contrast the fertility of the Stewarts of Scotland with the infertility of the Tudors.

As we walk round the various monuments in the Chapel one of the most striking things, apart from the magnificence of the two royal tombs, is the number of pure puzzles and surprises we meet with. If we are expecting this chapel to be dedicated simply, as its name suggests, to the royal successors of the first Tudors, we might be surprised at the number of monuments to persons whom we do not recognize either as Tudors or as monarchs. Prominent among those is the Countess of Lennox, for what – a visitor may well ask – is this tomb to a Scottish countess doing in a chapel dedicated to the Tudor succession? And the first thing to recognize is that this monument antedates all the others, for Margaret Douglas, who died in 1578, had been commemorated with this memorial that same year, 25 years before King James came on the scene. But although she gained her Scottish title after marriage to Matthew Stewart, 3rd Earl of Lennox, Margaret Douglas herself was daughter of Margaret Tudor, daughter of K. Henry VII, and Margaret Tudor’s marriage to James IV of Scotland is what gave her Scottish Stewart descendants their claim to the English throne should the Tudor bloodline fail. The fact that both Stewart and Tudor blood flowed through her own veins is what gave her son, Henry Darnley, the status which he claimed in marrying Mary Queen of Scots –– indeed this is what allowed Darnley to assume that on marrying Mary he had equal status with her on the throne of Scotland, with fatal consequences as he found to his cost. So you can see why, on deciding to locate the tombs of both Mary and Elizabeth in the Henry VII Chapel, King James might well have felt that the tomb of the Anglo-Scottish Countess of Lennox, who combined both Tudor and Stuart bloodlines – and was, indeed, his own paternal grandmother (for Darnley was, of course, his Dad) – stood as a perfectly seemly precedent for the two new monuments he was intent on building to Marie Stuart and Elizabeth Tudor. As Peter Sherlock says, “Although James had no role in the construction of the Lennox tomb, its convenient location and message about his father’s status and lineage provided a foil to his mother’s monument” (2007, p.281).

The Henry VII Chapel is indeed the closest Mary Queen of Scots ever came to meeting with her sister queen Elizabeth of England, but the placement of their two monuments in separate North and South Aisles of the Chapel has to be seen as making fundamental dynastic distinctions. What distinguishes the tombs closest to Mary’s in the South Aisle is indeed their emphasis on fruitful generation and childbirth, as we can see with the two adjoining monuments to James’s two daughters, Sophia and Mary, both of whom died in infancy. Students of British history may be excused for never having heard of these two royal children, but in 1606 Queen Anna gave birth to a daughter Sophia, who only lived for three days, and in 1607 another daughter, Maria, survived – as her monumental inscription informs us – for just two years, five months and eight days. Despite the fact that they did not live to play any part in British history, James commissioned splendid monuments by Maximilian Colt to their memory, of which Sophia’s must be one of the most extraordinary tombs not just in Westminster Abbey but almost anywhere, for the three-day-old infant is shown lying peacefully in her cradle. This design surely testifies to the grief of her royal parents, but in displacing the monuments to his two immediate predecessors on the English throne in favour of his two deceased infant daughters, James is surely accentuating his own marital fertility, which contrasts with that of his two predecessors on the English throne both of whom died without issue. King James’s readiness to permit Henry Howard, whom he had ennobled as 1st Earl of Northampton in March 1604, to inscribe on his mother’s monument the Latin verses which commemorated the late Queen of Scots as a Catholic martyr thus becomes less surprising, and the fact that noone hitherto has apparently recognized the fact suggests that the risk was worth taking.

Professor Michael Bath

Westminster Abbey, 13/02/20

This Emblem of the Month is based on a talk given by Prof Michael Bath in Westminster Abbey to Friends of the Abbey, in December 2019.

Leave a Reply